Just yesterday, I realized that this was my Francesca Woodman Summer.

In the Summer of 1980, at 22, Woodman ventured to New York City to establish herself as a photographer just after graduating from RISD. That Summer, she sent out her work to people in the fashion and art worlds, though her solicitations led nowhere. Her portfolio contained over 10,000 negatives. While she mixed formats, she favored the 6x6 negatives, so assuming an average (of her dabbling between large and 35mm) to medium format would mean she shot more than 833 rolls of film before she lept from a window on the East Side of Manhattan, ending her life that following January.

As it often goes, her work received accolades and acclaim after her death.

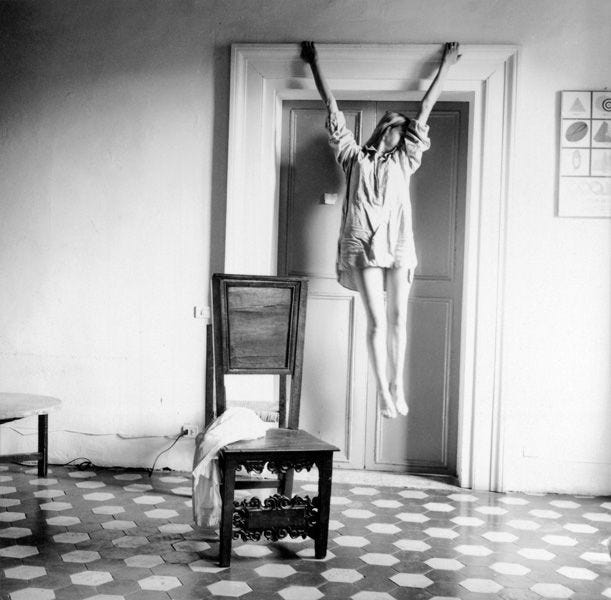

From Francesca Woodman: On Becoming an Angel

While not currently grappling with depression, I find myself in a similar season to hers: 22 years old, unemployed, and desperately striving to carve a path for myself. I've sent over 200 applications to various creative job openings, but they've all led to dead ends so far. The em-dash between graduation and the uncertain future has become a surreal, bloated, and phantasmagorical liminal space—at times, this reality has made me question the merit in even trying, though today I have hope.

Woodman's work inspired much of my own. While I don't consider myself primarily a photographer, my writing and art, much like others, come from the confessional space of my life—it seems unavoidable. She taught me how to place and obscure myself within a work, manipulate form and gesture, and ultimately, how we can say much about ourselves through self-portraiture without resigning to a modernized delusion of grandeur.

From Francesca Woodman: On Becoming an Angel

Through her long, double-exposed images, she crafts an ephemeral distance, a migration between an impression of self and the tangible reality of the body. My boyfriend, a believer in truth and objectivity, once said her work is impossible not to understand. Perhaps 'understand' isn't the right word, though Woodman's oeuvre evokes a sempiternal sense of transcendental dread tinged with an escapist desire to flee the frame. While melancholic, her work carries a sense of mystical enchantment through the lens, a manipulation of time (predating Photoshop), and a rebellion against the medium meant to capture and document one's reality. All earnest art aspires to accomplish this.

I refer to this period as my Francesca Woodman Summer, not as a proclamation that I'll meet a similar fate in the winter, but as a reflection of the parallels between her life and mine—both of us 22, freshly graduated, longing for success in a seemingly impenetrable field, eager to achieve self-realization at an accelerated pace.

Especially in our post-modernist age, there lies an incessant drive to create, become, produce, and establish ourselves as fully self-actualized human beings and artists, as if one day we become our true selves and remain that way for the rest of our lives. It feels redundant to reiterate how the internet and social media breed a sense of comparison. However, as creatives, the act of comparison comes not only from ourselves versus others but from employers. We face relentless pressure to prioritize quantity over quality, especially when our value to employers is often measured by our social media following and digital influence rather than our skill, passion, and the quality of work we've produced in the past.

As I grow a little older, I contemplate the accomplishments of artists, prodigies, and savants as I journey through the years. It's a frequent occurrence to come across stories of extraordinary success at a tender age, exemplified by the astounding case of the French poet Arthur Rimbaud. Remarkably, he only wrote poetry from 1870 to 1875, spanning the ages 16 to 21, before embarking on a different, more evil path.

What about 22—the repetitive digits, the precipice between two seasons, not quite tangible by 23 nor 24, yet by 25, I might be expected to have my life together to the point of wearing matching socks every day and teaching my dog to perform Lay Down, Play Dead, and Heel gracefully. Teaching the command Speak could be argued as an accomplishment by age 30, but who knows? I may have a cat.